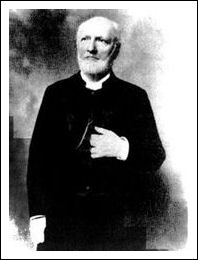

Yesterday. I quoted nineteenth century theologian-historian Philip Schaff (1819–1893), a Swiss-born, German-educated Reformed Protestant minister who became a widely regarded church historian at the end of his life. Schaff spent most of his adult life living and teaching in the United States. His works are still read though his history is now dated by the simple fact that he died in 1893.

Philip Schaff, along with John Williamson Nevin, were the highly regarded leaders of what became known as Mercersburg Theology. This Mercersburg Movement began in the mid-nineteenth century in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, the home of Marshall College from 1836 until its merger with Franklin College (Lancaster, PA), in 1853. It was the home for the seminary of the Reformed Church in the United States (RCUS) from 1837 until its relocation to Lancaster in 1871. This seminary was connected to what was known as the German Reformed Church, a church family that eventually merged into a union that became the Evangelical and Reformed Church. In 1957 the Evangelical and Reformed Church merged with the Congregational Christian Church, a decision which led to the modern United Church of Christ. (Today the UCC is, generally speaking, very liberal theologically.)

Philip Schaff, along with John Williamson Nevin, were the highly regarded leaders of what became known as Mercersburg Theology. This Mercersburg Movement began in the mid-nineteenth century in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, the home of Marshall College from 1836 until its merger with Franklin College (Lancaster, PA), in 1853. It was the home for the seminary of the Reformed Church in the United States (RCUS) from 1837 until its relocation to Lancaster in 1871. This seminary was connected to what was known as the German Reformed Church, a church family that eventually merged into a union that became the Evangelical and Reformed Church. In 1957 the Evangelical and Reformed Church merged with the Congregational Christian Church, a decision which led to the modern United Church of Christ. (Today the UCC is, generally speaking, very liberal theologically.)

Although the Mercersburg Seminary was located at Marshall College the aforementioned Mercersburg Theology movement really began in earnest in 1844 with the hiring of Philip Schaff. Schaff joined John Williamson Nevin (1803–1886) on the faculty in that year. The two became a dynamic duo for this new movement that I would eventually come to see as a forerunner of what I call missional-ecumenism. Schaff sparked off a controversy with his inaugural address in 1844, an address that was later published as Principle of Protestantism. (This is a book that I deeply value.) This pre-Civil War controversy led to a series of articles written against Professor Schaff’s views by a fellow RCUS pastor named Joseph Berg. Several other magazines attacked Schaff and Nevin over their controversial position concerning the relationship of the Reformed churches to the Roman Catholic Church. (The RCUS was divided on the issue.) The Philadelphia Classis (which is, in effect, the Reformed name for what the Presbyterian Church calls a presbytery) condemned Schaff’s theology. The East Pennsylvania Classis defended it. The Synod (which is a wider governing body consisting of several classis) took up this contentious issue in 1845. Schaff was cleared, along with his book, Principle of Protestantism, by a vote of 37 to 3! This marked the only time that Schaff was ever formally brought before the Synod on heresy charges but it was not the last time that he would face opposition from within the Reformed Church and beyond. The Synod ruled that further complaints had to be registered with the Board of Visitors (trustees) of the Mercersburg Seminary. This action established a principle that never allowed any more complaints to go before the Synod for trial. Schaff was criticized throughout his life for his “compromising stance toward the Catholic Church” but he persisted and continued to urge a new reformation in action and spirit. (I cannot overstate how the awareness of these issues impacted both my thinking and living in the years since I first read this material in the 1980s.)

When I first came to embrace what I now happily call missional-ecumenism it was Philip Schaff and John Williamson Nevin who gave me the theological insight to see how this vision of the wider church might work if orthodox categories were maintained in a spirit of unity and mission. In many ways I owe a great deal to these two giants.

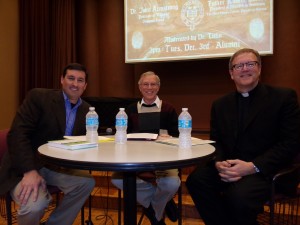

My dialogue with Fr. Robert Barron, at Moody Bible Institute yesterday (12/3/13), came about, in the long term sense, because I saw a model for this kind of discussion about the gospel and unity in these two pioneering spirits. They were both the heirs of the German/Swiss Reformation. Many modern (rigid) Calvinists have no place for this kind of theological understanding and work because they honestly think they would betray their own convictions if they engaged in serious dialogue with Catholic Christians, in some cases even with non-Reformed Protestants. (In the mid-1990s I experienced this firsthand and found it deeply discouraging!) Philip Schaff held an entirely different view of this matter. Tomorrow I will give an explanation of his view, a view that has helped me for several decades to publicly pursue wider dialogues in Christian love.

My dialogue with Fr. Robert Barron, at Moody Bible Institute yesterday (12/3/13), came about, in the long term sense, because I saw a model for this kind of discussion about the gospel and unity in these two pioneering spirits. They were both the heirs of the German/Swiss Reformation. Many modern (rigid) Calvinists have no place for this kind of theological understanding and work because they honestly think they would betray their own convictions if they engaged in serious dialogue with Catholic Christians, in some cases even with non-Reformed Protestants. (In the mid-1990s I experienced this firsthand and found it deeply discouraging!) Philip Schaff held an entirely different view of this matter. Tomorrow I will give an explanation of his view, a view that has helped me for several decades to publicly pursue wider dialogues in Christian love.

LifeCoach Gwen Griffith liked this on Facebook.

@JohnA1949 must recover that branch of Reformed theology. Thanks again!

RT @JohnA1949: The Mercersberg Movement: How Reformed Theology Helped Me Become a Missional-Ecumenist: Yesterday. I q… http://t.co/dmgaVy…

Thanks for this, John. Mercersberg has been a powerful influence on my own life–especially, in my case, the work of Nevin. We need to keep this legacy alive!

Dear John,

Thank you for sharing this background info on Philip Schaff.

Back in 2003, when I returned to the Catholic Church after a 25 year absence, I read something about Schaff and purchased “The Principle of Protestantism”. At the time, I was looking for a “bridge” between Evangelical Christianity and Catholic Christianity, since I loved them both.

I had a difficult time getting into it and didn’t get too far. I just pulled it off the shelf and will have another go at it; thanks to your introduction!

May Grace and Peace be multiplied to you,

_Rick

Greetings John. Glad to see this post. Here’s a short piece I wrote for Church History a while back. http://www.churchhistory.org/blogs/blog/category/adam-borneman/

[…] who recently participated in Catholic-Evangelical conversation at Moody Bible Institute, credits Mercersburg theology for his pursuit of what he calls missional-ecumenism. There are also scholarly organizations […]

[…] who recently participated in Catholic-Evangelical conversation at Moody Bible Institute, credits Mercersburg theology for his pursuit of what he calls missional-ecumenism. There are also scholarly organizations […]