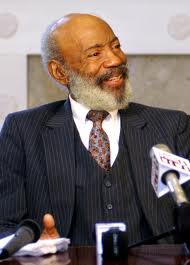

James Meredith, in spite of all he went through as a young man in his 20s and 30s, has lived an anything but dull life and he has seen great joy in his children and grandchildren, much as I have. One of Meredith’s sons not only graduated from Harvard but won the 2002 Outstanding Doctoral Student award at Ole Miss in the School of Business Administration. James says his entire time at Ole Miss was a “grotesque insult and humiliation” until the day his son received his doctorate. He also has twin sons who received degrees at Philips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, while his second wife (they married after his first wife died quite young) received a degree from Mississippi State University. But Meredith says, in reflection, that the hardest part of life is “growing old. I feel like I am thirty-eight, but I look in the mirror and I see a guy cruising into his eighties” (233). He gave his personal papers to Ole Miss in 1997 and the school built a five-hundred-pound bronze statue of him to celebrate what happened on campus in the early 60s. When he gave a lecture an old professor offered this opinion, “He is a man of incredible courage. He is also, in some ways, as nutty as a fruitcake. A very strange man. But he has more guts that a violin factory” (234).

In 2006 the statue I referred to above was formally dedicated. Congressman John Lewis, a true civil rights hero, gave a speech in which he said, “This is a monument to the power of peace to overcome violence.” Meredith says he disagreed completely.

Near the end of his rather amazing (and amusing) book he says, “The statue of me on the campus of the University of Mississippi must be torn down immediately” (238). Meredith has asked the university to destroy it but no one believes him or honors this wish. His reason is not humility. Here is his rather amazing conclusion about the bronze statue:

Any other objections to the statue pale beneath the most important one of all: It is a violation of God’s law. “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,” which is known as the Second Commandment. The James Meredith statue is a false idol. It must be destroyed and ground to dust (239).

Meredith writes that he has many regrets. He wishes he had done more to advance the cause of fellow Mississippians, white and black. His greatest regret, in his own words, is “that I have not done nearly enough to help America’s poor, and especially its poorest black citizens” (246). He is not a champion for government driven welfare but a champion of work and dignity! His greatest passion is for better and more effective education. He says, “The human condition of poor blacks in America is far beyond a failure or a disaster; it has become a real-life, flesh-and-blood horror movie” (246). The tendency of some blacks is to blame all of this one someone else but James Meredith thinks otherwise. “It’s what we’ve not done for us” (247). OI how I wish people across the political spectrum would read this book and hear this elderly man’s poignant and clear vision.

He believes the major problem is the breakdown of education for the poor. He gives several pages of moving prose to explain this plight and ends with his simple challenge for all of America:

I challenge every American citizen to commit right now to help children in public schools in their community, especially those schools with disadvantaged students.

Meredith says these twenty-five words, if acted upon, would create a revolution of love in our country that will transform our nation, uplift our children, and help America lead the world (252). What moves me personally is that my son is deeply involved in doing precisely one part of the work in the public schools that Meredith envisions. I am not sure how but Matt had a passion for America’s children, especially poor children, from the time he was an early teen. If you have not seen his mission previously check it out at Crossroads Kids Club.

I would have to guess that many of you who read these words would argue with Meredith’s claim about public education. Though I too could provide some very simplistic negatives toward his vision I think he is fundamentally correct. Where I have seen people, especially Christians of deep and abiding faith, get involved with children in our public schools the results have been nothing short of amazing. He says there are countless ways you can help. I agree. Regardless of your politics get involved. Take risks for the kingdom and invest your life in children – one child at a time. Stop expecting an election to solve this problem and get involved. You might do more but you can do no less if you care about our collective future as a nation.

Related Posts

Comments

My Latest Book!

Use Promo code UNITY for 40% discount!

Enjoyed your blog post