My recent blogs have been devoted to developing a perspective I refer to as missional-ecumenism. I want to show where I believe we are in America today–particularly in terms of the church, culture and our mission. I am a passionate missional-ecumenist. This passion is deeply rooted in three principal texts, all found in the Fourth Gospel; John 13:34-35, 17:20-23 and 20:21. What we discover in the Fourth Gospel is that God is a trinity of loving persons who created humankind in his image. The Father sent the Son into the world to redeem the whole cosmos (cf. Colossians 1:15-20). He is now recreating us by the Spirit, forming a unified redeemed people into a community of faith, hope and love. In this theological paradigm the church is the mission of God (missio Dei), a mission that reveals God’s love as we live faithfully in community. This means the church is not an institution that does mission so much as it is a people who are mission! (This does not mean we ignore missions and missionaries, as some have argued. We must always keep our strong focus on those unreached with the good news.)

Because of the paradigm I see revealed in these three texts in John’s Gospel I humbly submit that ecumenical theology is one of the most pressing needs in our time. I believe this is true precisely because the church that is not profoundly committed to the unity of all the church in Christ’s mission is not seriously committed to the most urgent item of healthy missiology in our century. Let me elaborate.

If the gospel is to be liberated from a Western scientific worldview on the one hand, and from fundamentalism on the other, then it would be helpful if we understood how we actually got to this point in Western history. How did the big ideas that drove both modernism and fundamentalism, and both are the product of the same big ideas, become central to the life and practice of the Christian faith? And what can be done to resist these deadly two ditches so that we can actively promote the kind of missional-ecumenism that is centered in the gospel itself, not in our rational propositions about faith and theology?

Since very few [women] were allowed to enter ordained ministry, the vast majority had to content themselves with a vocation of domestic care. In a complete reversal of the medieval and Reformation understanding of women, they were no longer regarded as vortexes of barely contained sexual and emotional energy that must constantly be mastered, but as the “weak sex” – kind, gentle, submissive, passive, self-sacrificing and asexual. Men, who were now more likely than women to be regarded as only a step away from being “beasts,” must be protected from their baser instincts by women’s ministrations and good example. Women must have them. Such ideals were communicated not only by male preachers and teachers, but by the thousands of evangelical journals and magazines that were avidly devoured by nineteenth-century women readers. They took vivid shape in stories of virtuous womanhood that figured largely in such literature, in which tales were told of women who, by sheer moral and spiritual force, saved the men they loved from the sinful lives into which they were falling. Their reward, in many cases, was not only a sense of spiritual triumph, but the love of the man they had saved (An Introduction to Christianity, Linda Woodhead, Cambridge University Press, 2004, 250).

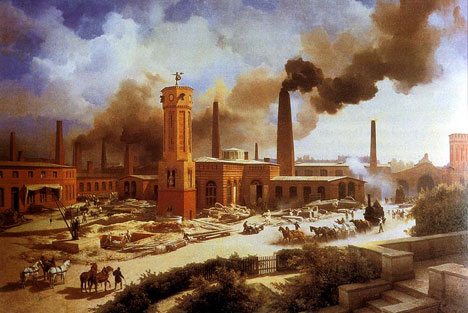

Out of this socially changing context sex-roles, at least so far as I understood them growing up in the conservative 1950s, were significantly evolving. This was a development that also unfolded over the course of decades but it would eventually lead many conservative Christian leaders to defend a stereotyped 1950s role for men and women as the biblical model for the role of women. The irony of this reaction is that in earlier centuries in America men and women had shared the household duties. It was only in the growing industrial society that men left home to go to work while women stayed at home and cared for the family. “The churches played a key role in this process, not least in making this contingent state of affairs natural and God-given. . . . mainstream Christianity allied itself with patriarchal interests to develop ideological justification for male exclusion of women from the new economic and spiritual opportunities that presented themselves” (An Introduction to Christianity, 251). Women were now instructed to remain in the home and serve their husbands and children without pay. Working-class women were forced to enter the work place but their jobs resulted in menial pay for their employment. By these developments the more radical Protestant Reformation idea of the “priesthood of all believers” was subverted once again. But the story has only just begun. Tomorrow we will see what all of this meant to theology and mission.

Related Posts

Comments

Comments are closed.

My Latest Book!

Use Promo code UNITY for 40% discount!

Dan Tomberlin liked this on Facebook.